Don’t Call It a Comeback!

Most people know zines aka fanzines aka fan magazines for their punk, DIY aesthetic and the important role they played in counterculture communities around the 70s, 80s, and 90s. Although the first of these homemade booklets were produced in 1930, decades before then. So how exactly did they get their reputation as mostly punk mini-magazines?

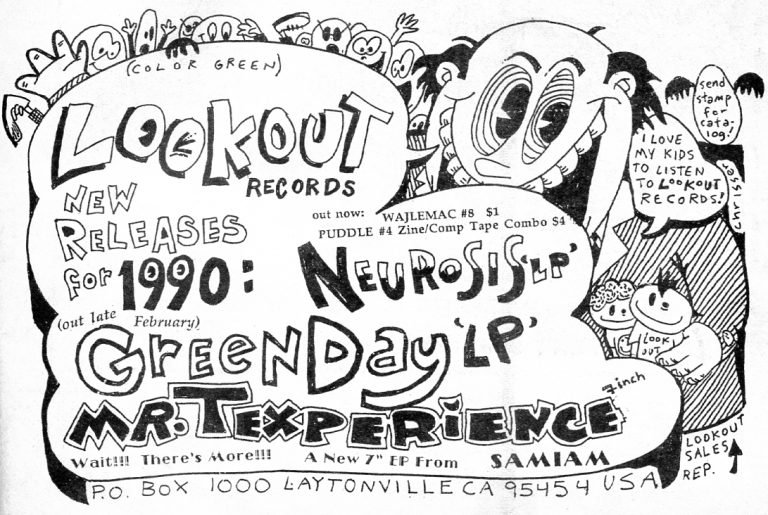

East Bay Area flyer ~1990

A promo flyer for Lookout! Records, the independent, punk record label that’s best known for releasing Green Day ‘s first version “album” (aka a compilation of their first four EPs) containing the first version of their hit, Welcome to Paradise!

I personally became familiar with zines as a young teen, observing them on display or for sale at the punk venues I frequented. (924 Gilman being one of them! And a lot of grimier ones that are no longer around.) This was sometime during the early 2000s in the East Bay Area, California. Self-published, uncensored, and community-based, the zines I encountered were most often about politics, philosophy, music, and art. The doodles and handwritten essays made them feel personal. Some promoted local bands, upcoming events, and it was a way for photographers to distribute the badass photos of last week’s show. Some issues could universally resonate and were timeless, while others were so specific to the region/era that it would make little to no sense to someone who wasn’t present at specific events.

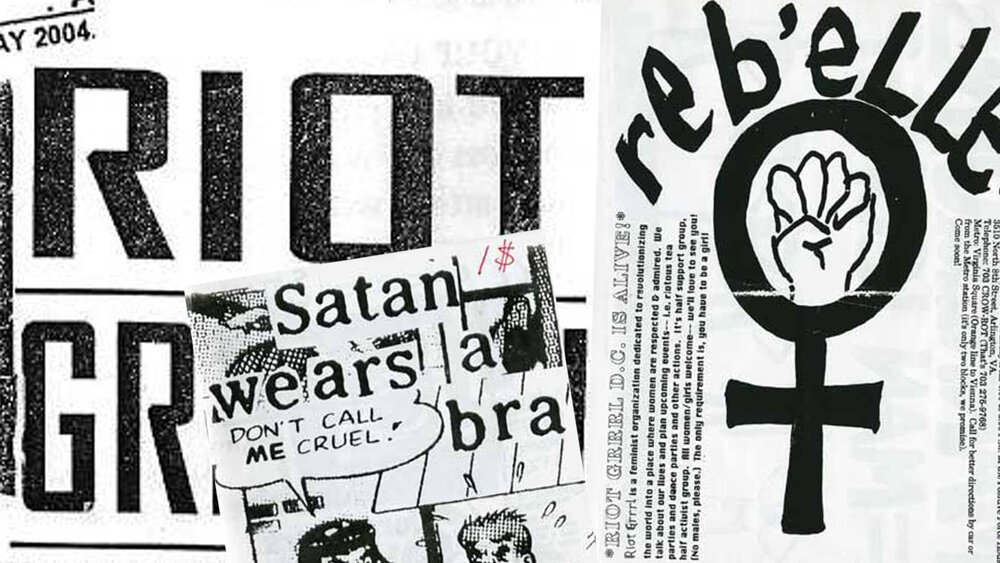

It would be a few years of being involved in my own local punk scene, before I would find myself scrolling on Tumblr, discovering one of the most well-known punk movements that zines helped facilitate: Riot Grrrl. This movement happened in the 90s (yes, it was very white lol) and pushed third-wave feminist messages of sex positivity, valuing femme friendships, and more, in their raw punkrock songs. In 1991, the Riot Grrrl Manifesto was written by Kathleen Hanna, the lead singer of a band called Bikini Kill, and was published in the second issue of Bikini Kill’s self-titled zine. Bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile fronted this movement and weren’t performing by the time I was a teenager, so seeing these aesthetics and concepts from issues that came out in the past while scrolling online in the 2000s,was like discovering something new.

The raw aesthetics of the Riot Grrrl content matched the rough sound of the genre’s music, something I still look for in almost all art I consume. I did see Babes in Toyland (which is debatably a “Riot Grrrl” band but was very much active in the 90s!) more than a few times, but it wasn’t the same. (Not in a bad way.) And of course, seeing newer bands that were at all similar was simply experiencing the influence and inspiration of the movement.

The Riot Grrrl aesthetic I found on Tumblr differed from those zines I saw in my younger years, proving that these self published publications were immortalizing a specific era. Reblogs of old zines gained international traction; and I wonder now if some of the people responsible for those impactful scribbles (not everyone who contributed were lead singers of well known bands) knew that one day there would be a digital revival. They would be a part of history. (2011 Tumblr-me would call it herstory.)

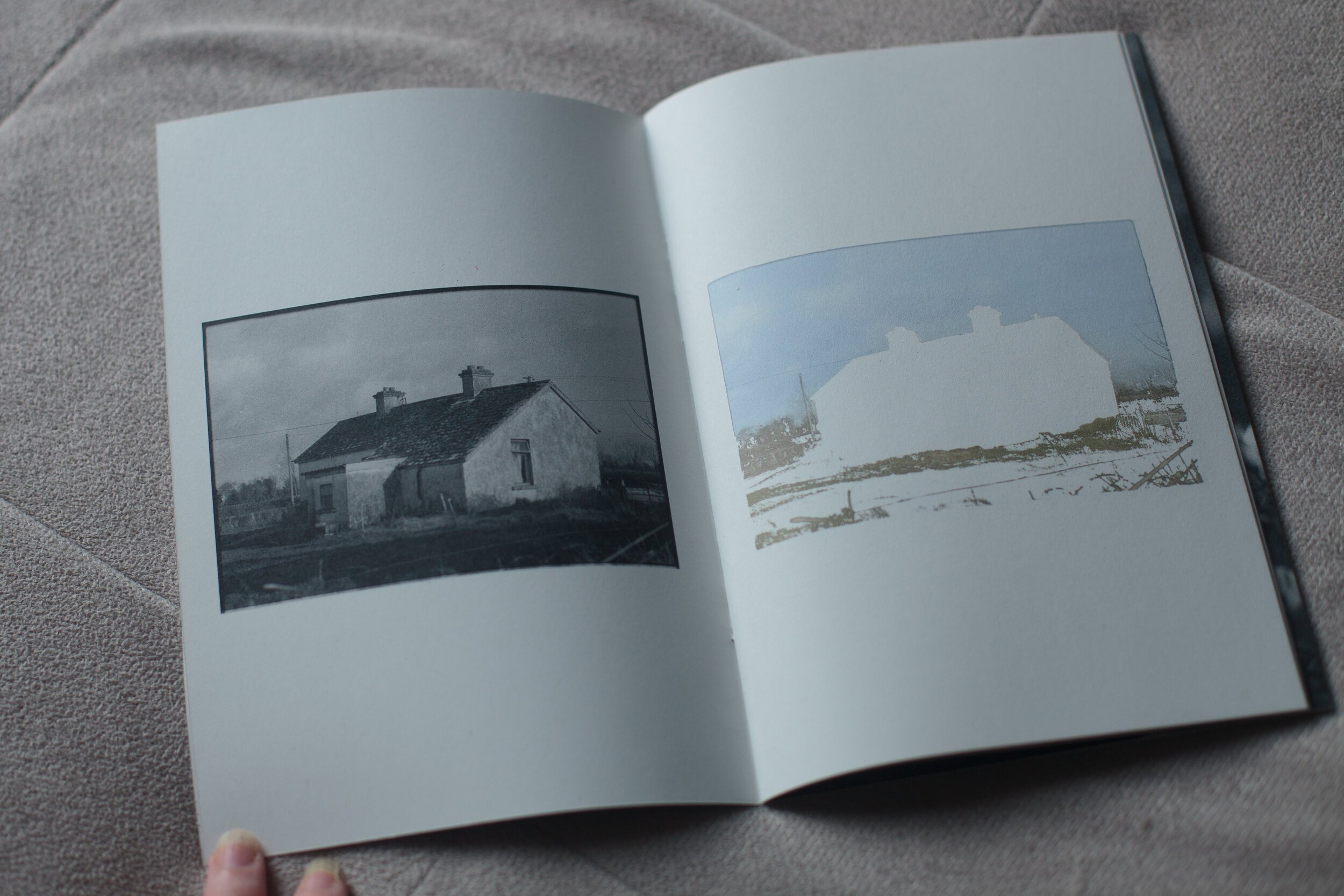

The zine-making process is an extremely simple one—making it easy for people to publish various creative works themselves. Accessibility was a leading factor in the appeal of zine culture, especially when people didn’t have the Internet or if they lacked resources. It wasn’t uncommon for popular zines to be inexpensively made by using only black sharpie and being completely hand drawn. They would often contain manifestos, comics, collections of poems, art, essays, guides, and anything else you can think of.

The range of how zines can look and what they can contain truly has no bounds. There are neat, clean, digitally created issues as well… And that is just part of the beauty of this medium.

Some chose to distribute their zines within their friend groups or interest groups, others chose to sell subscriptions, and some chose to donate them. These indie-made mini-magazines (think a DIY magazine and a pamphlet’s baby…) offered a creative freedom that came with not relying on major publishing companies. They inspired broad based participation from communities that appreciated the intimacy of self-publishing and rejected mainstream processes.

Let’s goooo back, back to the beginning… (Yes, I listened to punk, but I also listened to Hilary Duff.)

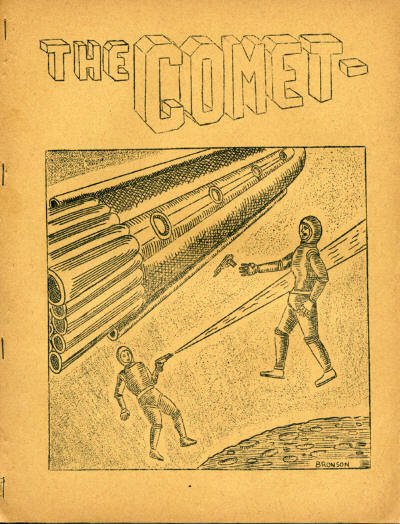

The first zine was created in 1930 and was published by The Science Correspondence Club, a science interest group. The very first issue was called The Comet, and The Club continued to regularly put out issues featuring news about their shared interest, and had a letter section that contained contributions from their subscribers– adding an element of community.

At that time, photocopiers weren’t invented yet, so stencils and printing presses were used to produce these homemade zines in a time efficient manner– partially contributing to the style we relate to zines today. One stencil/press could be used hundreds, or even thousands, of times and being efficient was important since these were do-it-yourself publications.

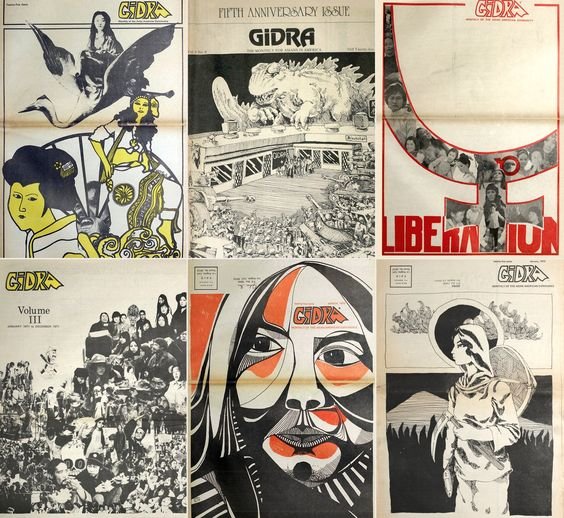

By the 60s people were using zines to spread messages of social and political activism, so it’s unsurprising that punks and other community-based, anti-establishment subcultures gravitated toward this form of media. Again, the lack of censorship and creative freedom allowed people a form of expression that wouldn’t be possible otherwise.

By the 90s, zines had solidified their role in punk and underground, anti-establishment culture. Consuming content from small, noncorporate publications felt community-based and direct.

The popularity of zines has fluctuated since the beginning of their existence, but some say zines are making a comeback. They declined in popularity when the internet made it even more accessible to blast information with the click of a button, but the art of zines never truly died. Some things you can’t replace and that was proven when I experienced Riot Grrrl on Tumblr, years later from across the nation. I even got a tattoo that says “Every Grrrl Is a Riot Grrrl!” (The movement was very centered on cis women and white women. I wanted to reject the notion that trans women or women of color should be excluded, while still honoring what I thought was revolutionary about the movement.)

Whether to make a political statement, or show off your photography, zines are still a fun way to express and share your works. There are still zines being made and distributed to this day, and they probably won’t go away any time soon.

I’ve been wanting Avril Heals to host a zine workshop for a while, but I was unsure of how to execute it. Thankfully, my lovely friend, and Avril Heals community member, Billie Blossom, has experience in leading zine-making workshops, and has offered to teach us how to make our very own zines!

Bring a sharpie or some pens, some paper, and we’ll start documenting our own histories–or just doodle!